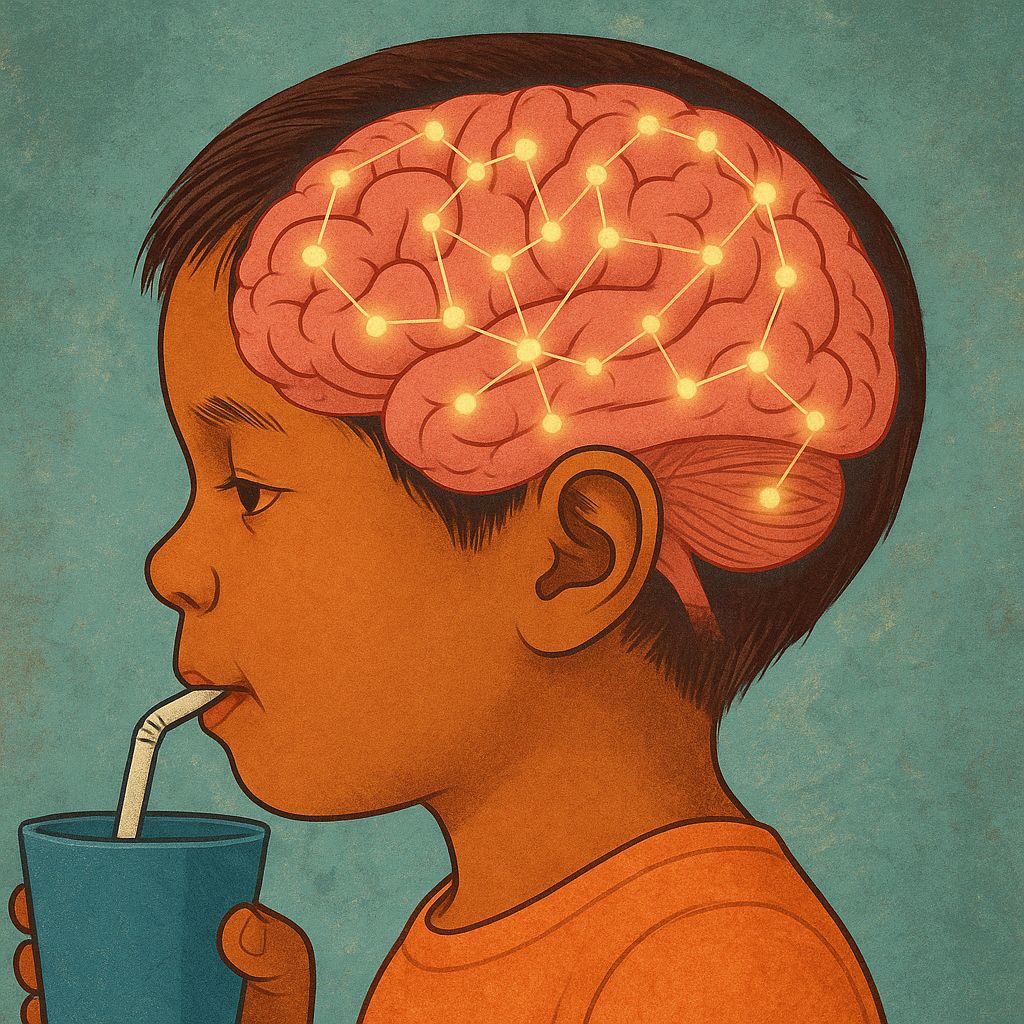

New research is shedding light on how excessive sugar consumption in childhood might rewire the brain in ways that last well into adulthood. A study published in Current Biology found that mice exposed to a high-sugar beverage from weaning developed long-term changes in brain activity and behavior, even though their body weight and glucose tolerance remained normal. A feature in Nature highlights how these findings could deepen our understanding of the neurodevelopmental impact of early dietary patterns.

In the study, one group of mice received a sugary beverage, while another got plain water. As adults, the sugar-exposed mice showed weaker brain responses to sucrose and slower activation of learning-related areas. Connections between different brain regions were also reduced, suggesting that early sugar intake can alter how the brain processes information and adapts over time.

Both groups learned the task, but the sugar-fed mice reacted more strongly when reward patterns changed. This heightened sensitivity points to subtle shifts in cognitive flexibility — how the brain adjusts to new situations — which could have lasting effects in more complex environments.

These findings underscore how sensitive the developing brain is to diet. By showing that early sugar exposure can reconfigure neural networks involved in learning and reward, the study provides a real-world example of brain plasticity: the ability of experience to shape neural circuits. Over a century ago, Santiago Ramón y Cajal —often regarded as the father of modern neuroscience— already stated that “Every man can, if he so desires, become the sculptor of his own brain”. The research and the Nature feature echo that insight, showing that what children consume can leave deep, lasting marks on brain function.

This work pushes the conversation beyond sugar’s link to obesity or diabetes. It suggests that early diet can affect the brain’s adaptability itself. That opens the door to solutions: lowering added sugar in childhood diets, creating nutrition policies that prioritize brain development, and exploring ways to strengthen healthy neural pathways through enriched environments and balanced nutrition.

Because young brains are especially malleable, early interventions can do more than prevent harm — they can actively build healthier neural pathways. This study is a reminder that feeding the developing brain is not just about calories; it’s about shaping the foundations of future learning and adaptability. Ensuring that children grow up with balanced diets and supportive environments is, ultimately, an investment in the architecture of their minds.

Coordinator at la Verneda-Sant Martí Learning Community and adjunct professor at the University of Barcelona