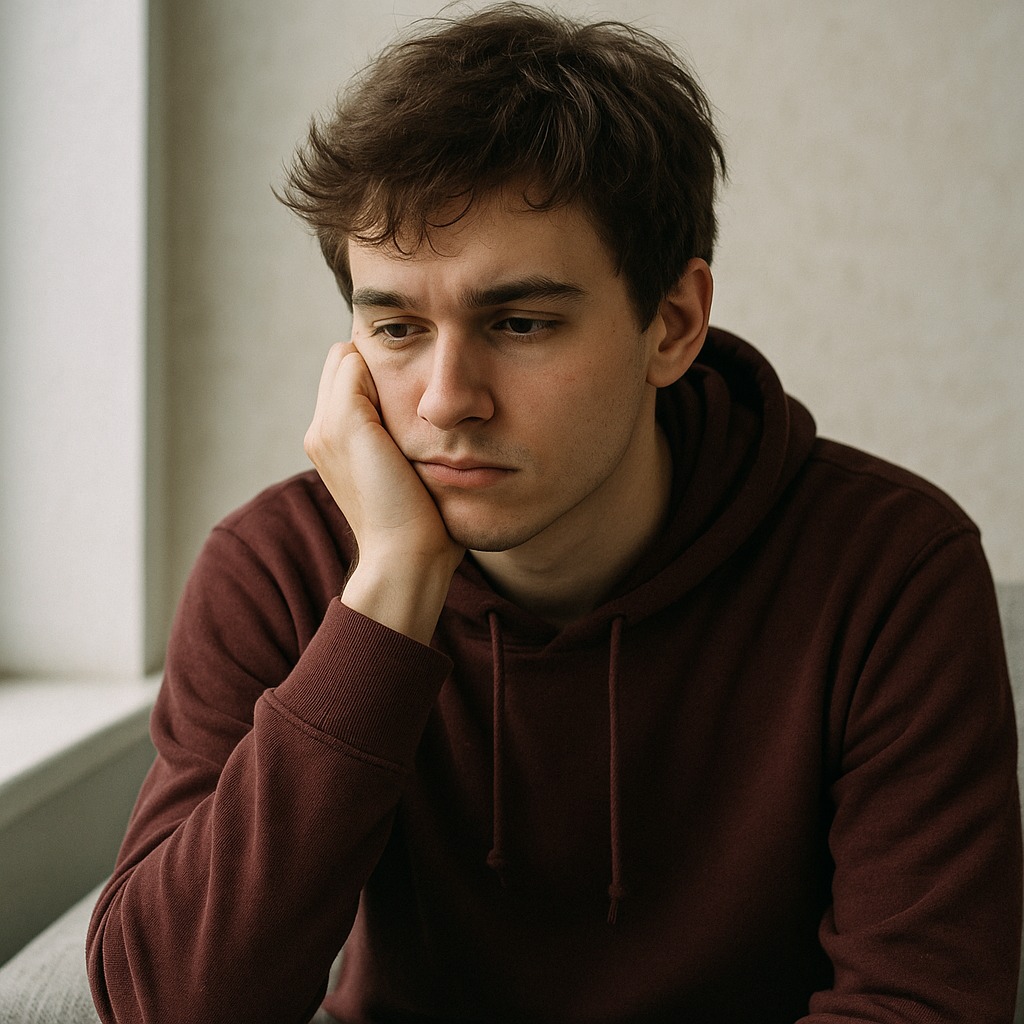

We often imagine loneliness as a quiet inconvenience of old age — but science paints a different picture. Loneliness is emerging as a major public health risk, with effects on par with smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity. And far from only afflicting the elderly, it hits hardest among young adults —79% of those between the ages of 18 and 24 reported feeling lonely, compared with 41% of people aged 66 and older— and marginalized communities, challenging long-held assumptions.

A feature in Nature explains why loneliness is so damaging and, crucially, how we can transform our environments and behaviors to counter it. Chronic loneliness doesn’t just feel bad — it physically reshapes the brain and body. Research links it to higher risks of cardiovascular disease, dementia, depression, weakened immunity, and even premature death. Neuroimaging studies show changes in areas tied to motivation, reward, and memory. One striking finding: the brain’s response to social deprivation mirrors its response to hunger — signaling an unmet biological need to reconnect.

Yet loneliness also distorts our perceptions, making social interactions seem more threatening or less rewarding, and trapping people in a self-reinforcing cycle. This burden falls disproportionately on young adults, racial minorities, and those with lower incomes — revealing loneliness not only as a personal issue, but as a social and structural one.

The good news is that change is possible. Walking just a few kilometers has been shown to improve mood, interrupt negative thought patterns, and help reset the brain’s social circuits. Initiatives like Walk with a Doc, which combines exercise with social interaction, demonstrate how even modest interventions can break the cycle. More broadly, cities and institutions can foster connection by creating shared spaces, supporting inclusive programs, and ensuring that vulnerable groups have equitable access to social opportunities. Some examples of community evidence-based actions such as Dialogic Literary Gatherings done in collaboration with health services which promote friendship and solidarity relationships, countering loneliness, have already been published in this journal.

What this research makes clear is that loneliness is neither inevitable nor insurmountable. By acknowledging it as a serious condition with profound biological impacts —and by redesigning our environments to make connection easier and more rewarding —we can turn a silent crisis into a catalyst for healthier, more resilient communities.

Coordinator at la Verneda-Sant Martí Learning Community and adjunct professor at the University of Barcelona