When we think about the dangers of alcohol, we tend to point to ethanol. But what if the real enemy were hidden in the grape?

Wine is much more than a drink: it is heritage, identity, ritual. Its consumption, especially in Mediterranean countries, is associated with well-being and even relaxing properties. However, in scientific contexts, we must look at it with different eyes: not just as an alcoholic beverage, but as a complex chemical matrix.

From neurotoxicology—the discipline that studies how certain substances affect the nervous system—we ask ourselves an uncomfortable question: what else are we drinking without knowing it?

As part of a recent study at the Institute of Environmental Assessment and Water Research (IDAEA-CSIC), we analyzed the impact of a common pesticide in viticulture: the fungicide boscalid. This substance, routinely applied in vineyards, inhibits succinate dehydrogenase, an essential enzyme in cellular metabolism present not only in fungi, but also in fish, insects, and humans. In other words, it is a biological target that has been conserved throughout evolution.

Concentrations of boscalid, similar to those detected in surface water after agricultural treatments—in the order of micrograms per liter, which is roughly equivalent to dissolving one-fiftieth of a grain of salt in a bottle of water—caused changes in heart rate and alterations in the response to stimuli in three aquatic species: zebrafish (Danio rerio), medaka (Oryzias latipes), and water fleas (Daphnia magna), changes in heart rate, alterations in response to stimuli, and modifications in key neurotransmitters involved in memory, learning, and stress response. These effects do not imply acute toxicity in the classical sense (mortality, infertility, developmental problems), but they do imply physiological and neurobehavioral disruptions that endanger the survival of organisms in their environment. Currently, our regulatory tools may be underestimating the real impact of compounds such as boscalid. Wine, beyond ethanol, could be a vector for chemical residues capable of altering deeply conserved cellular functions. As consumers and citizens, we have the right—and the responsibility—to know what is really in our glass. The time has come to reconsider chemical risk and commit to viticultural practices that are safer for the environment and human health.

This is not alarmism, but evidence. Toasting should always be a celebration… not an uninformed experiment.

References

-Bedrossiantz, J., Goyenechea, J., Prats, E., Gómez-Canela, C., Barata C., Raldúa, D. (2024). Cardiac and

neurobehavioral impairments in three phylogenetically distant aquatic model organisms exposed to

environmentally relevant concentrations of boscalid. Environmental Pollution, 328, 123685.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123685

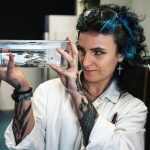

I am a neuroscientist and toxicologist. I use video tools to explore the behavioral and physiological effects of neuroactive compounds in aquatic models as D. rerio, D. magna, O. latipes or D. labrax.

Passionate about translational science, I am currently involved in the development and validation of photopharmaceuticals as new therapies. In parallel, I coordinate several educational and science outreach programs, with the firm conviction that science should be accessible and inclusive.