International Holocaust Remembrance Day

Forty five years after he was allowed to return to Germany as a Romany concentration camp detainee, Paul Winterstein told me: “I’m a salesman and sometimes there are still days, for example, when I’ve got some customers, and I notice that someone decides not to buy something on account of my appearance. Then, even after all these years, I still feel bitter. You have to put up with a lot, but I’ve learnt to cope with that.”

In May 1940, Paul and family, he a tiny child at the time, had been deported to a labour camp in Poland along with two and a half thousand German Sinte. So ideologically important was the ‘expulsion’ of the German Sinte and Roma that this original deportation was announced in September 1939, less than a month after the start of the war. Politicking in the newly occupied territories and logistics delayed the transports but when it came this represented the very first deportation of German citizens beyond the borders of the Reich. It was to provide a model for all that were to follow.

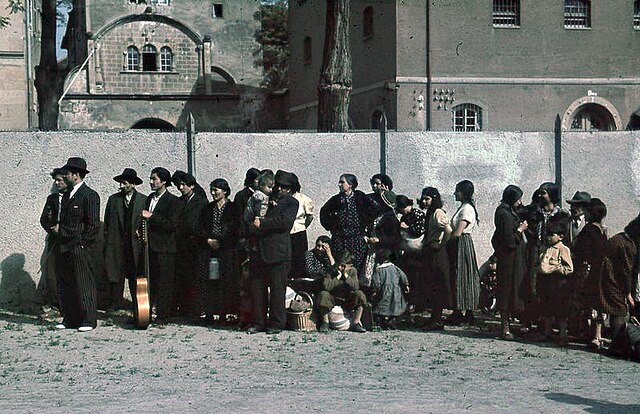

We have records of this early deportation because the police in one of the three towns where the Gypsies were assembled, before being put onto trains east, took a careful photographic record of how they proceeded to move a thousand people through the city of Karlsruhe in broad daylight without alarming the local population. They were using the romany victims a guinea pigs for the Jewish deportations to come.

By the end of the war, in every country the Nazis had occupied Gypsies, like Jews, had been persecuted because of their birth. By the end of the war, two thirds of Germany’s thirty thousand Roma and Sinte, a greater proportion of Austrian, Czech and Croatian romany people and tens of thousands elsewhere, were dead. Of those who remained in Germany, many had been sterilised, others had been crippled through slave labour. Although it is still extremely hard to put precise figures on the total number of dead, it seems that at least 200,000 Romany people and maybe many more were killed as a direct consequence of racial policies pursued by the German state and its various allies in Italy, Croatia, Romania, the Baltic States and on the eastern front.

The Romany peoples were persecuted because the Nazis – like many ordinary German civil servants – believed that ‘Zigeuner’ stood outside ‘respectable’ society because their nature was ‘asocial’. They were declared ‘aliens to the national community’. Because the Nazis often avoided the language of race when dealing with Romany people (though you were declared a Gypsy by birth), after the war most compensation claims were rejected. Romany people were told that their persecution represented legitimate security measures, necessary in time of war (sterilisation and internment in concentration camps included).

For the Romany people there was no Israel. They would be stuck in the lands where they had suffered so badly. The trauma of non-recognition has haunted these communities across Europe ever since. Paul’s sterilised brother, Herbert, who had also lost his hearing in the camps described the everyday anguish of coming back to live again amongst his tormentors. “You never really know where you stand. You never know who was a Nazi and who wasn’ t. It’s best just to say: ‘Good day, have a nice day.’ And if they then let it show that they were Nazis, then it makes you boil with anger.”

PhD from the LSE in 1988 based on fieldwork in Hungary with Rom, has taught Anthropology at Cambridge, Budapest, Vienna and at UCL in London. Since 2014 he has been Professor of Anthropology at UCL and founded both the Open City Documentary Festival there as well as the collaboration between anthropologists and creative practitioners at UCL known as ‘Public Anthropology.’ He is currently completing a comprehensive history of the persecution of Europe's Romany peoples 1933-1945 and the campaigns for restitution and acknowledgement afterwards. Publications include The Time of the Gypsies (Perseus).