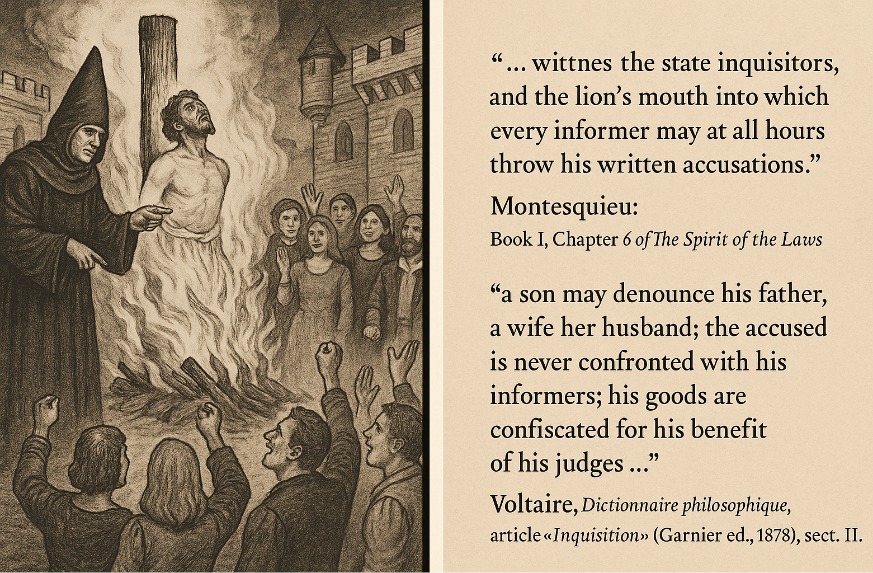

When people think of the Inquisition, they usually imagine the horror of the stake. That image sparks rejection, but it also hides other inquisitorial practices that, in different forms, survive to this day. One of the most notorious was the secrecy of denunciations.

Juan Antonio Llorente, who served as secretary of the Inquisition and later wrote its critical history, warned that anonymous accusations “allowed private enemies to disguise their resentment as zeal for the faith, and turned the Inquisition into an instrument of private vengeance.” Montesquieu summed it up in The Spirit of the Laws: “… witness the state inquisitors, and the lion’s mouth into which every informer may at all hours throw his written accusations.” Voltaire was equally blunt: “a son may denounce his father, a wife her husband; the accused is never confronted with his informers; his goods are confiscated for the benefit of his judges …”.

Today we also see forms of anonymity, which should not be confused with legitimate confidentiality. These practices are often coupled with another old inquisitorial idea: that “the truth is not discovered but guarded”. Behind many modern populisms are interest groups disguised as ideology, convinced they hold the truth and entitled to impose it. And just as in the past, they end up driven by envy, vengeance, and the will to dominate—the same flaws already denounced by Llorente, Montesquieu, and Voltaire.

1st with the most total citations of all categories, among those authors including in Google Scholar "Gender Violence" as one of them.